The Looting of India

Author and MP SHASHI THAROOR in his book An Era of Darkness comes up with a well-researched critique of East India Company’s rule over India, to demonstrate how it crippled India’s economy. An extract:

In 1930, a young American historian and philosopher, Will Durant, stepped onto the shores of India for the first time. He had embarked on a journey around the world to write what became the magnificent eleven-volume The Story of Civilization. But he was, in his own words, so ‘filled with astonishment and indignation’ at what he saw and read of Britain’s ‘conscious and deliberate bleeding of India’ that he set aside his research into the past to write a passionate denunciation of this ‘greatest crime in all history’. His short book, The Case for India, remains a classic, a profoundly empathetic work of compassion and outrage that tore apart the self-serving justifications of the British for their long and shameless record of rapacity in India. As Durant wrote:

The British conquest of India was the invasion and destruction of a high civilization by a trading company [the British East India Company] utterly without scruple or principle, careless of art and greedy of gain, over-running with fire and sword a country temporarily disordered and helpless, bribing and murdering, annexing and stealing, and beginning that career of illegal and ‘legal’ plunder which has now [1930] gone on ruthlessly for one hundred and seventy-three years.

The Conquest of India by a Corporation

Taking advantage of the collapse of the Mughal empire and the rise of a number of warring principalities contending for authority across eighteenth-century India, the British had subjugated a vast land through the power of their artillery and the cynicism of their amorality. They displaced nawabs and maharajas for a price, emptied their treasuries as it pleased them, took over their states through various methods (including, from the 1840s, the cynical ‘doctrine of lapse’ whenever a ruler died without an heir), and stripped farmers of their ownership of the lands they had tilled for generations. With the absorption of each native state, the Company official John Sullivan (better known as the founder of the ‘hill-station’ of Ootacamund, or ‘Ooty’, today known more correctly as Udhagamandalam) observed in the 1840s: ‘The little court disappears—trade languishes—the capital decays—the people are impoverished—the Englishman flourishes, and acts like a sponge, drawing up riches from the banks of the Ganges, and squeezing them down upon the banks of the Thames.’

The India that the British East India Company conquered was no primitive or barren land, but the glittering jewel of the medieval world. Its accomplishments and prosperity—‘the wealth created by vast and varied industries’—were succinctly described by a Yorkshire-born American Unitarian minister, J. T. Sunderland:

Nearly every kind of manufacture or product known to the civilized world—nearly every kind of creation of man’s brain and hand, existing anywhere, and prized either for its utility or beauty—had long been produced in India. India was a far greater industrial and manufacturing nation than any in Europe or any other in Asia. Her textile goods—the fine products of her looms, in cotton, wool, linen and silk—were famous over the civilized world; so were her exquisite jewellery and her precious stones cut in every lovely form; so were her pottery, porcelains, ceramics of every kind, quality, color and beautiful shape; so were her fine works in metal—iron, steel, silver and gold.

She had great architecture—equal in beauty to any in the world. She had great engineering works. She had great merchants, great businessmen, great bankers and financiers. Not only was she the greatest shipbuilding nation, but she had great commerce and trade by land and sea which extended to all known civilized countries. Such was the India which the British found when they came.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, as the British economic historian Angus Maddison has demonstrated, India’s share of the world economy was 23 percent, as large as all of Europe put together. (It had been 27 percent in 1700, when the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s treasury raked in £100 million in tax revenues alone.) By the time the British departed India, it had dropped to just over 3 percent. The reason was simple: India was governed for the benefit of Britain. Britain’s rise for 200 years was financed by its depredations in India….

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, as the British economic historian Angus Maddison has demonstrated, India’s share of the world economy was 23 percent, as large as all of Europe put together. (It had been 27 percent in 1700, when the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s treasury raked in £100 million in tax revenues alone.) By the time the British departed India, it had dropped to just over 3 percent. The reason was simple: India was governed for the benefit of Britain. Britain’s rise for 200 years was financed by its depredations in India….The nabobs of Cotswolds

Tharoor also throws light on the caprice of the company officials who made vast fortunes during their postings in India

The Cockerell brothers, John and Charles, both of whom served the East India Company in the second half of the eighteenth century, built an extraordinary Indian palace in the heart of the Cotswolds, complete with a green onion-shaped dome, umbrella-shaped chhatris and overhanging chhajjas, Mughal gardens, serpent fountains, a Surya temple, Shiva lingams—and with Nandi bulls guarding the estate. The mansion, Sezincote, designed by a third Cockerell brother, the architect Samuel Pepys Cockerell (who, unlike his siblings, had never been to India), still stands today, an incongruous monument to the opulence of the nabobs’ loot.

The Deindustrialization of India: Taxation, corruption & The ‘Nabobs’

The British government assisted the Company’s rise with military and naval resources, enabling legislation (prompted, in many cases, by the Company’s stockholders in Parliament), loans from the Bank of England and a supportive foreign policy that sought both to overcome local resistance and to counter foreign competitors like the French and Dutch. But as the Company’s principal motive was economic, so too were the major consequences of its rule, both for India and for Britain itself.

Britain’s Industrial Revolution was built on the destruction of India’s thriving manufacturing industries. Textiles were an emblematic case in point: the British systematically set about destroying India’s textile manufacturing and exports, substituting Indian textiles by British ones manufactured in England. Ironically, the British used Indian raw material and exported the finished products back to India and the rest of the world, the industrial equivalent of adding insult to injury.

The British destruction of textile competition from India led to the first great deindustrialization of the modern world. Indian handloom fabrics were much in demand in England; it was no accident that the Company established its first ‘factory’ in 1613 in the southern port town of Masulipatnam, famous for its Kalamkari textiles. For centuries the handloom weavers of Bengal had produced some of the world’s most desirable fabrics, especially the fine muslins, light as ‘woven air’, that were coveted by European dressmakers. As late as the mid-eighteenth century, Bengal’s textiles were still being exported to Egypt, Turkey and Persia in the West, and to Java, China and Japan in the East, along well-established trade routes, as well as to Europe. The value of Bengal’s textile exports alone is estimated to have been around 16 million rupees annually in the 1750s, of which some 5 to 6 million rupees’ worth was exported by European traders in India. (At those days’ rates of exchange, this sum was equivalent to almost £2 million, a considerable sum in an era when to earn a pound a week was to be a rich man.) In addition, silk exports from Bengal were worth another 6.5 million rupees annually till 1753, declining to some 5 million thereafter. During the century to 1757, while the British were just traders and not rulers, their demand is estimated to have raised Bengal’s textile and silk production by as much as 33 per cent. The Indian textile industry became more creative, innovative and productive; exports boomed. But when the British traders took power, everything changed.

The British government assisted the Company’s rise with military and naval resources, enabling legislation, loans from the Bank of England and a supportive foreign policy.

In power, the British were, in a word, ruthless. They stopped paying for textiles and silk in pounds brought from Britain, preferring to pay from revenues extracted from Bengal, and pushing prices still lower. They squeezed out other foreign buyers and instituted a Company monopoly. They cut off the export markets for Indian textiles, interrupting long-standing independent trading links. As British manufacturing grew, they went further. Indian textiles were remarkably cheap—so much so that Britain’s cloth manufacturers, unable to compete, wanted them eliminated. The soldiers of the East India Company obliged, systematically smashing the looms of some Bengali weavers and, according to at least one contemporary account (as well as widespread, if unverifiable, belief), breaking their thumbs so they could not ply their craft.

Crude destruction, however, was not all. More sophisticated modern techniques were available in the form of the imposition of duties and tariffs of 70 to 80 per cent on whatever Indian textiles survived, making their export to Britain unviable. Indian cloth was thus no longer cheap. Meanwhile, bales of cheap British fabric—cheaper even than poorly paid Bengali artisans could make—flooded the Indian market from the new steam mills of Britain. Indians could hardly impose retaliatory tariffs on British goods, since the British controlled the ports and the government, and decided the terms of trade to their own advantage.

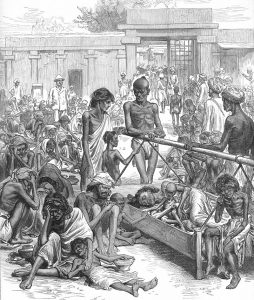

India had enjoyed a 25 per cent share of the global trade in textiles in the early eighteenth century. But this was destroyed; the Company’s own stalwart administrator Lord William Bentinck wrote that ‘the bones of the cotton weavers were bleaching the plains of India’….

India had enjoyed a 25 per cent share of the global trade in textiles in the early eighteenth century. But this was destroyed; the Company’s own stalwart administrator Lord William Bentinck wrote that ‘the bones of the cotton weavers were bleaching the plains of India’….

The destruction of artisanal industries by colonial trade policies did not just impact the artisans themselves. The British monopoly of industrial production drove Indians to agriculture beyond levels the land could sustain. This in turn had a knock-on effect on the peasants who worked the land, by causing an influx of newly disenfranchised people, formerly artisans, who drove down rural wages. In many rural families, women had spun and woven at home while their men tilled the fields; suddenly both were affected, and if weather or drought reduced their agricultural work, there was no back-up source of income from cloth. Rural poverty was a direct result of British actions….

Extraction and taxation and diamonds

But the ill effects of British rule did not stop there. Taxation (and theft labelled as taxation) became a favourite British form of exaction. India was treated as a cash cow; the revenues that flowed into London’s treasury were described by the Earl of Chatham as ‘the redemption of a nation…a kind of gift from heaven’. The British extracted from India approximately £18,000,000 each year between 1765 and 1815. ‘There are few kings in Europe’, wrote the Comte de Chastelet, French ambassador to London, ‘richer than the Directors of the English East India Company.’

Taxation by the Company—usually at a minimum of 50 per cent of income—was so onerous that two-thirds of the population ruled by the British in the late eighteenth century fled their lands. Durant writes that ‘[tax] defaulters were confined in cages, and exposed to the burning sun; fathers sold their children to meet the rising rates’. Unpaid taxes meant being tortured to pay up, and the wretched victim’s land being confiscated by the British. The East India Company created, for the first time in Indian history, the landless peasant, deprived of his traditional source of sustenance….

Corruption, though not unknown in India, plumbed new depths under the British…. Everybody and everything, as the 1923 edition of the Oxford History of India noted, was on sale.

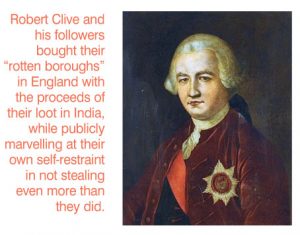

Colonialists like Robert Clive, victor of the seminal Battle of Plassey in 1757 that is seen as decisively inaugurating British rule in India, were unashamed of their cupidity and corruption. On his first return to England Clive took home £234,000 from his Indian exploits (£23 million pounds in today’s money, making him one of the richest men in Europe). He and his followers bought their ‘rotten boroughs’ in England with the proceeds of their loot in India, while publicly marvelling at their own self-restraint in not stealing even more than they did.

Clive came back to India in 1765 and returned two years later to England with a fortune estimated at £400,000 (£40 million today). After accepting millions of rupees in ‘presents’, levying an annual tribute, helping himself to any jewels that caught his fancy from the treasuries of those he had subjugated, and reselling items in England at five times their price in India, Clive declared: ‘an opulent city lay at my mercy; its richest bankers bid against each other for my smiles; I walked through vaults which were thrown open to me alone, piled on either hand with gold and jewels… When I think of the marvellous riches of that country, and the comparatively small part which I took away, I am astonished at my own moderation.’

And the British had the gall to call him ‘Clive of India’, as if he belonged to the country, when all he really did was to ensure that a good portion of the country belonged to him.

Lead Picture: Britishers engaged in multiple wars with Indian rulers to plunder their wealth and resources. Photo: www.uridiot.com

No comments:

Post a Comment